Feltleaf willows: Alaska’s most abundant tree

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

May 25, 2023

Feltleaf willow leaves emerge beneath where a moose nipped off buds during the winter of 2022-2023 in Fairbanks.

Imagine being a moose in late May: You have just survived 200 days of cold and darkness by munching the equivalent of a large garbage bag full of frozen twigs each day.

Now, billions of salad greens are unfolding from those same woody plants, providing a scent and texture savored for an instant before one sweep of the moose’s head strips a wispy branch. All over Alaska, moose are sucking in new leaves like whales inhaling plankton.

The most plentiful moose food in the state — and probably Alaska’s most numerous tree — is the feltleaf willow, which was once called the Alaska willow.

As its name implies, the feltleaf sprouts canoe-shaped green leaves that feel fuzzy on the underside. Most of the feltleaf willows in Alaska are in areas disturbed by moving rivers, melting glaciers, and human cuts for roads, houses and parking areas. They prefer as much sunshine as they can get.

A catkin stands from the stem of a feltleaf willow, preparing someday this summer or fall to release airborne willow seeds in tiny capsules carried by fluff.

People would call the majority of these carbon dioxide-absorbing plants shrubs, as the tallest are just 30 feet high. Millions of them are much smaller, resembling fields of orangey old-fashioned car antennas sprouting from gravel bars of big and small waterways.

Willows like the feltleaf (there are more than 30 species in Alaska, many hard to tell from one another) are the little engines that make the northern forest go. The leaves — and in winter the bark — are a major source of protein for moose. Snowshoe hares — 3-pound bundles of stringy muscle and a touch of fat — eat the bark, leaves and small twigs. Willow ptarmigan grow plump from buds that have not yet burst as well as the leaves.

Single willows can survive moose nipping off 90 percent of their twigs. They reproduce by the chance meeting of male pollen produced by some willows wafting to female reproductive parts on others. After that union, caterpillar-like catkins form on the stems. Those catkins release capsules of seed to the wind on parachutes of fluff.

Willows can also reproduce without chance windborne sexual encounters: New plants sometimes sprout from stem fragments that find receptive soil after they are broken or snipped off. It’s probably safe to say that a handful of willows have reproduced in this vegetative fashion somewhere in Alaska as you are reading this.

If you want success as an Alaska gardener, the feltleaf willow seems a good choice. After the construction of the trans-Alaska pipeline, researchers with the University of Alaska Fairbanks School of Agriculture and Land Resource Management in 1977 led a team attempting to restore feltleaf willows to parts of the Atigun and Sagavanirktok river valleys. To lay the path of the pipeline and nearby roads, workers had extracted gravel from the beds of those waterways, uprooting many willows.

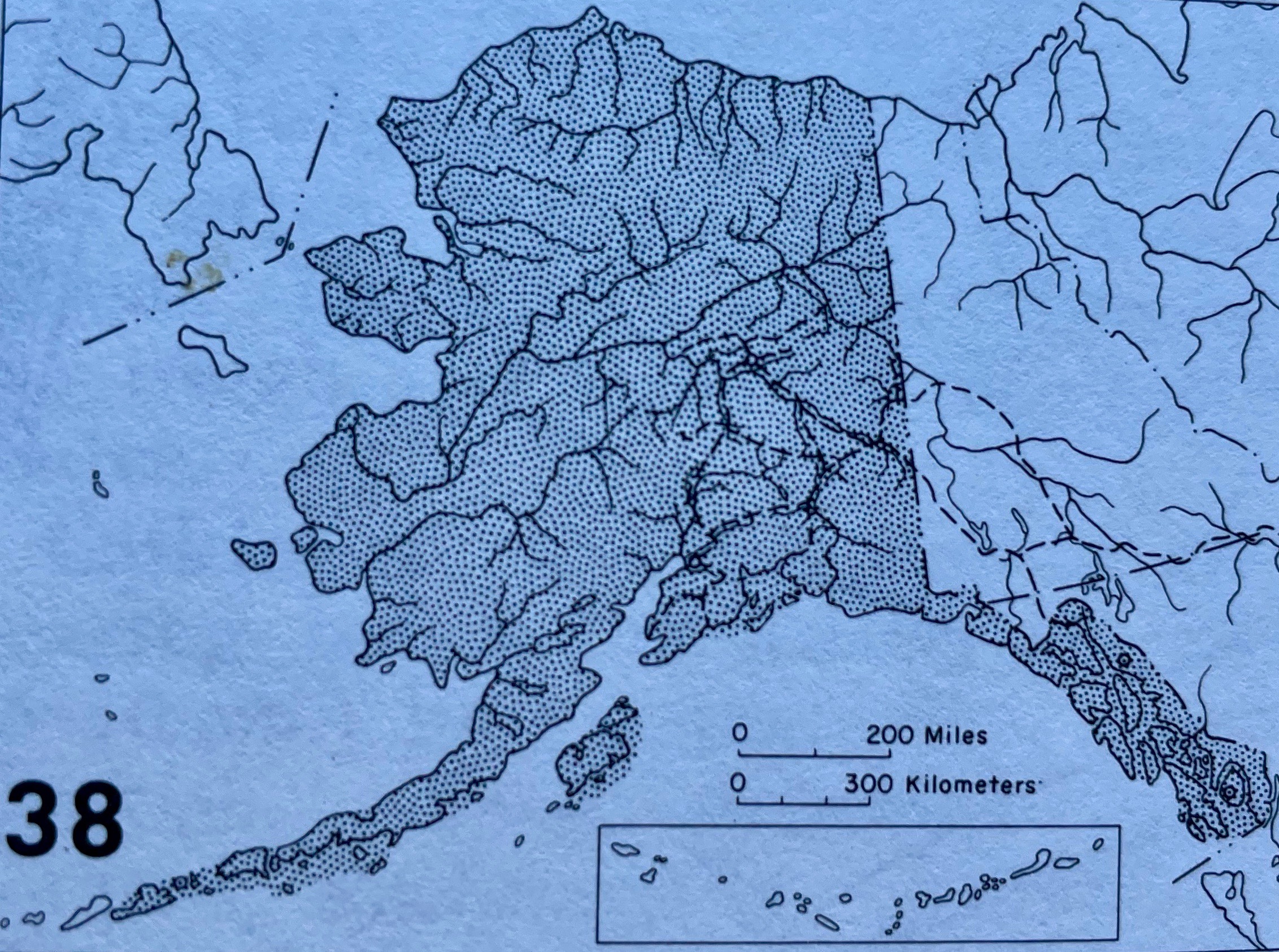

The range of the feltleaf willow, probably the most numerous tree in Alaska.

After hand-planting thousands of feltleaf willow whips in the disturbed river beds (primarily as a future food source for North Slope moose), the foresters returned nine years later. At their most successful site, more than half of their plantings had shot up into healthy tall shrubs.

Somewhere close to you, a feltleaf willow has recently grown a few millimeters in height while exhaling oxygen for your use. The plant is common just about everywhere in Alaska except for the Aleutians and a few other islands off the west coast. It exists southeastward in a wide buffer along the Alaska Highway and past Edmonton, Alberta, but does not grow in the Lower 48.

Since the late 1970s, the ĚŔÄ·ĘÓƵ' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.