Fun with ice physics in the cryosphere

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

Jan. 20, 2022

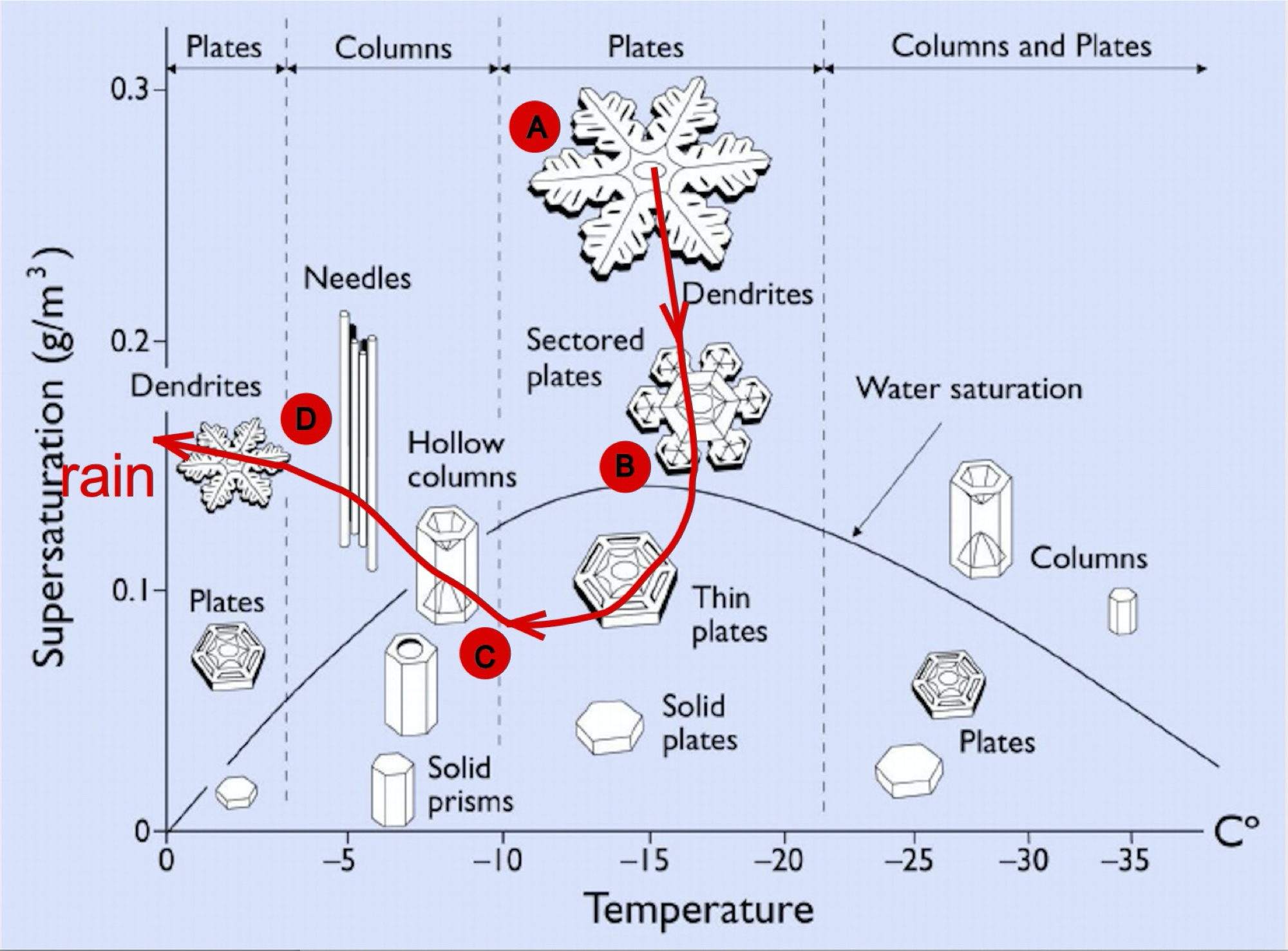

Matthew Sturm captured these images of snow crystals falling in a Dec. 26, 2021, storm in Fairbanks. Their shapes correspond to different temperatures and humidity within the cloud that formed them.

A recent winter storm that featured a heavy rainfall caused hardships for many animals

of Interior Alaska, but some people found the event fascinating.

Two men who live up here and study the cryosphere — the frozen and snow-covered portion

of the Earth’s surface — squinted for a closer look at what the storm threw at us.

When the snow-rain-snow storm began just after Christmas 2021, Matthew Sturm noticed

“exquisite” snow crystals falling on his deck in Fairbanks. He could see them without

a magnifying lens.

The snow scientist at UAF’s Geophysical Institute rushed inside to grab his microscope

camera. As the storm evolved and the air warmed, Sturm shot portraits of ice crystals

as they morphed at different temperatures to different, predictable shapes, and finally

to raindrops.

A Nakaya diagram showing the different shapes of snow crystals formed under different cloud conditions. A through D correspond to the crystal types Matthew Sturm photographed in a Dec. 26, 2021 storm in Fairbanks.

From the 1930s to 1960s, Japanese physics professor Ukichiro Nakaya studied both natural

and artificial snowflakes. He drew a diagram showing which frozen shapes formed at

a certain temperature and humidity within a cloud.

Scientists have since identified more than 100 forms of snowflakes, including stellar

dendrites that we perceive as the six-pointed perfect flake.

Sturm photographed different types of snowflakes during the recent storm, each of

which told him about what was happening in the clouds above. His interest in the subject

(Sturm has studied snow in Alaska, across the Arctic, and in Antarctica for 40 years)

helped him through a stretch when power was out to his home for 26 hours and his neighborhood

roads went unplowed for four days.

“It was a good break from shoveling heavy, wet snow,” he said.

As for those roadways, a Fairbanks commuter recently compared driving in town to the

tooth-rattling drive needed to reach McCarthy on the former bed of the Copper River

and Northwestern Railway.

A Fairbanks highway after a midwinter rain event. The crack in the asphalt pavement provided a weak point in the almost-uniform ice formation on the roadway. The bare areas are providing a bumpy ride for Fairbanks drivers, who may endure the conditions until April.

Fairbanks roads are now a rhythmically bumpy experience because rain that fell in

December coated the roads in an almost-uniform sheet of ice an inch thick. Where the

ice is mysteriously absent, ovals of bare asphalt appear at regular intervals.

Tom Douglas pondered the ice gaps while bashing his truck home one day in Fairbanks.

A permafrost expert with the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory

at Fort Wainwright, Douglas pulled over and looked at the slivers of the road not

covered with ice.

He noticed long cracks in the asphalt at the center of each of the ice-free sections.

He then asked ice physicists and engineers for their opinions.

Douglas summarized his colleagues’ responses:

When the rain fell on the supercooled surfaces of Fairbanks roads, it quickly turned

to ice. Since then, the roads have been a mostly continuous sheet because air temperatures

have been well below freezing since that weird rain event.

Ice that formed over those cracks in the road was less perfect than ice over the smooth

asphalt, and was more vulnerable to forces from above. We hammer at these faults as

we drive over them in our F-150s.

“Compressive stresses from car tires led to flexing, brittle fracture, and removal

of ice at these weak spots,” Douglas wrote.

Since the late 1970s, the ĚŔÄ·ĘÓƵ' Geophysical Institute has

provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell

is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.