Thirty years on semisolid ground

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

Jan. 27, 2022

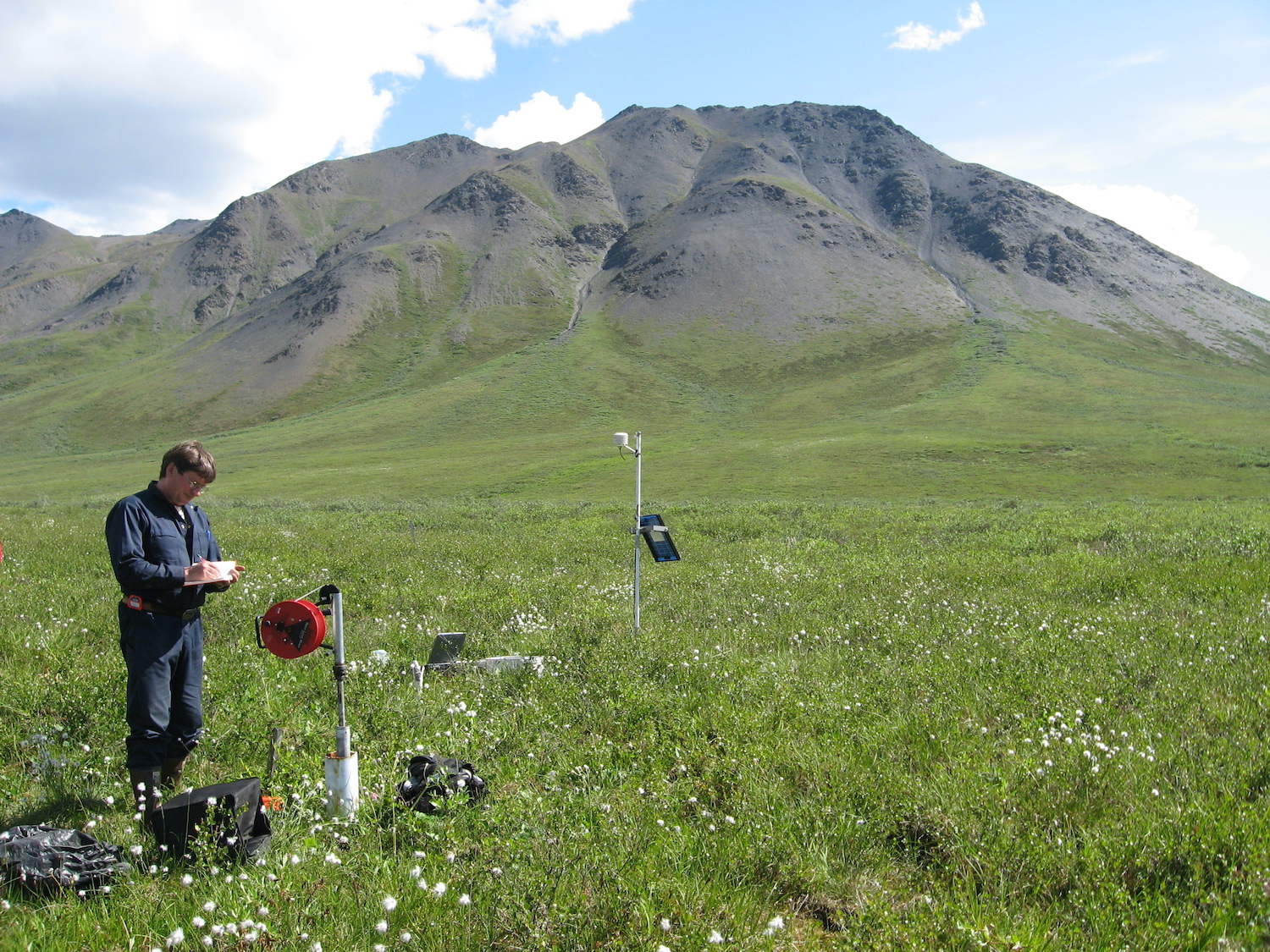

Vladimir Romanovsky works at a permafrost-monitoring site on Alaska’s North Slope in 2007.

At the end of this month, Vladimir Romanovsky will retire after 30 years as a professor and permafrost scientist at the Őņń∑ ”∆Ķ Geophysical Institute. This comes at a time when people ‚ÄĒ finally ‚ÄĒ no longer squint at him with a puzzled look when he mentions what he studies.

Permafrost is ground that has remained frozen through the heat of at least two summers. It is the consequence of a water-rich planet slinging through space about 93 million miles from its major heat source, the sun. That distance, along with the Earth’s tilt and rotation, has formed enduring ice and frozen soil beneath the northern ground surface. Permafrost is like a bank account that grows richer during the planet’s cold periods. We are now in a state of withdrawal.

Permafrost lies beneath 25 percent of lands north of the equator and under about 80 percent of Alaska.

When Romanovsky began studying the substance in the 1970s, he was also playing hockey at Moscow State University. Scientists then thought permafrost would be a stable indicator of the new ice age some thought was just ahead, following a cool period in the 1960s.

But something happened in 1976 -1977 to Alaska: air temperatures started trending warmer.

Tom Osterkamp, shown here at Bonanza Creek near Fairbanks, was Vladimir Romanovsky’s mentor who established permafrost-monitoring stations along the trans-Alaska oil pipeline.

Noticing that change, Romanovsky’s mentor at the Geophysical Institute, Tom Osterkamp, saw the new camps and airstrips being built for the trans-Alaska oil pipeline in the mid-1970s. He thought they would be splendid places to drill deep holes and drop in strings of thermistors. With them, he could monitor permafrost temperatures 200 feet deep along the pipeline, which runs 800 miles north-to-south across Alaska, making for a nice transect.

‚ÄúHe said ‚ÄėLet‚Äôs put these boreholes in when the warming is just starting, or maybe hasn‚Äôt even started yet,‚Äô‚ÄĚ Romanovsky said during a recent interview. ‚ÄúThat was a great idea and great implementation.‚ÄĚ

Because permafrost is beneath the ground surface and insulated by soil, plants, roots and other things, its temperature only reacts to long-term changes in climate. This has made Osterkamp’s monitoring sites, which he installed in the early 1980s, reliable indicators of a steadily warming North.

‚Äú(Permafrost temperatures) are the best indicators of climate change, I believe,‚ÄĚ Romanovsky said.

He said permafrost temperatures contrast with ‚Äúvery noisy‚ÄĚ air temperatures, which jump all over the place and require years of looking back for scientists to extract a useful signal.

Over the years, Romanovsky has faithfully returned to Osterkamp’s (who retired to Missouri in 1997) boreholes to download the last years’ temperature information. He has also established many other permafrost monitoring sites in Alaska and his native Russia.

In his three decades studying in Alaska, Romanovsky has witnessed something he never imagined: the permafrost beneath Alaska‚Äôs North Slope ‚ÄĒ in some places 2,000 feet deep ‚ÄĒ being touched by modern warm air.

‚ÄúFor years, everyone said ‚ÄėNorth Slope permafrost is stable,‚Äô‚ÄĚ he said, meaning that very far-north place would have a rock-solid foundation for years to come. ‚ÄúNow we are seeing it‚Äôs not as stable as we thought.‚ÄĚ

Scientists now think that by the end of this century, North Slope permafrost may thaw up to 15 feet beneath the ground in places. The sinkage and erosion that results won't be good news for the many roads and pipelines used by oil and gas industry workers up there. Nor anyone who depends upon northern oil and gas.

The destabilization of North Slope permafrost, evident in about 2015, has been the biggest surprise of Romanovsky’s Alaska career. Another big change has been peoples’ awareness of his usually out-of-sight study subject.

Workers gather around a thermokarst ‚ÄĒ a hole that opened up due to thawing permafrost beneath ‚ÄĒ behind a Őņń∑ ”∆Ķ building.

‚ÄúYears ago, when I was flying to Russia, passport agents would ask me what I do, and they would say, ‚ÄėWhat is permafrost?‚Äô‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúNow, I tell them what I do, and they say, ‚ÄėOh, it‚Äôs still here?‚Äô‚ÄĚ

Scientists estimate permafrost holds twice as much carbon as is currently in the air, which is a terrifying thought should all those ancient frozen roots and stems thaw and microbes go to work converting them to greenhouse gases.

But Romanovsky thinks the in-your-face consequences of permafrost thaw will strike first (and already have): the dollars spent to repair northern roads and houses, and the need to find new sites for villages located on crumbling, sinking ground.

Romanovsky remembered another change during his long career. In 2005, journalist Elizabeth Kolbert included him in a New Yorker story titled ‚ÄúThe Climate of Man.‚ÄĚ It was one of the first times a reporter went with him to his field sites.

‚ÄúTen years ago nobody cared about permafrost,‚ÄĚ he told Kolbert then. ‚ÄúNow everyone wants to know.‚ÄĚ

Even though he is retiring (and still playing hockey), professor emeritus Romanovsky wants to keep on telling people what he has learned in a career of thinking about and monitoring frozen ground.

‚ÄúAs many times as it‚Äôs possible, I will do it,‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúI think it is important.‚ÄĚ

Since the late 1970s, the Őņń∑ ”∆Ķ' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.