What does it take to reach 75?

The aurora borealis shines over Fairbanks. To a large degree, the Geophysical Institute at the ╠└─╖╩╙╞╡ owes its existence to the aurora.

Ned Rozell

907-474-7468

Aug. 26, 2021

We just had a party up here, to celebrate the Geophysical InstituteтАЩs 75th year of existence. Seventy-five years also happens to be the average life expectancy for a human these days.

A workplace for volcanologists, glaciologists, seismologists, aurora-ologists and other types of scientists, the Geophysical Institute at the ╠└─╖╩╙╞╡ has endured since the 1940s. Why?

As with anything that survives for three-quarters of a century, this place has had its share of good breaks. Here are a few elements that were pivotal to the Geophysical InstituteтАЩs early development:

Location: Fairbanks has its downsides, but it is a great place to study the aurora borealis, which forms an oval over the North Pole and is often visible when the sky is dark and clear.

Those winter nights and the existence of a university in middle Alaska were key factors when officials with the U.S. Department of Terrestrial Magnetism in 1931 funded an aurora study in Fairbanks. Well before the start of the Geophysical Institute, a physics professor used cameras spaced a dozen miles apart to determine the height of the aurora. Veryl Fuller found that the aurora appeared overhead from about 50 miles to 360 miles up.

That study тАФ the first-ever published at the university тАФ showed outside administrators (who had money to spend) that viable science could be executed in Alaska.

The Elvey Building (with the satellite dish on top), is home to the Geophysical Institute on the Troth Yeddha' Campus of the ╠└─╖╩╙╞╡.

Post-war financial support and enthusiasm for science: During World War II, military leaders noticed a problem that seemed to be connected to the aurora. The upper-atmospheric electrical disturbances that cause aurora displays could at times disable high-frequency radios that pilots and ship commanders used to communicate.

With that problem in mind just after the war, 75 years ago members of Congress passed an act тАЬto authorize an appropriation for the establishment of a geophysical institute at the University of Alaska.тАЭ With the act, Congress members awarded University of Alaska administrators $975,000 for the construction and establishment of what became known as the Geophysical Institute.

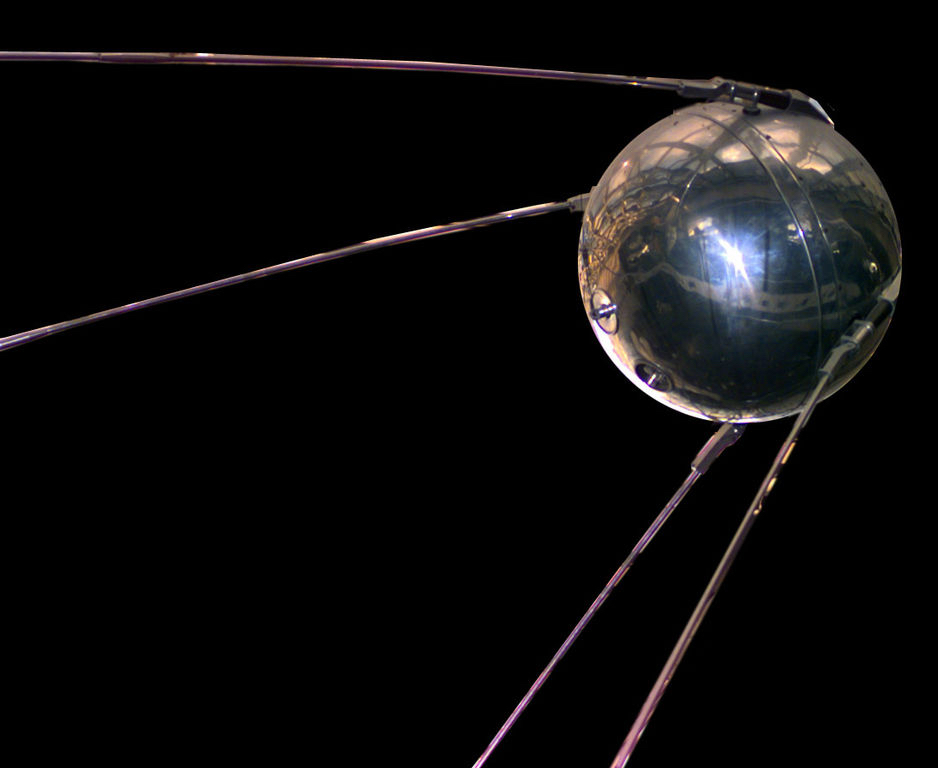

A replica of the first manmade satellite, Sputnik 1, hangs is in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The satellite, launched by the Russians in 1957 at the start of the Space Age, was first spotted above North America by observers from the UAF Geophysical Institute in Fairbanks.

Sputnik: On Oct. 4, 1957, humanity entered the Space Age when the Russians launched Sputnik 1, the first manmade satellite. The size of a beach ball and the weight of a person, Sputnik took about 98 minutes to complete a loop around the planet. Geophysical Institute students and researchers were the first Americans to detect the moving dot in the sky, from just north of the Fairbanks campus.

People wondered about the implications of the Soviet object looping over America every two hours. Within a year, Congress voted to create NASA. All the fuss was good news for the Geophysical Institute, which had a few dozen students and professors in place, interested in space and qualified to study it.

The recruitment of Sydney Chapman: Sydney Chapman was a diminutive British researcher who was a world authority in space physics and the lead author of the textbook, Geomagnetism, a classic in the field.

Geophysical Institute director William Wilson knew that Chapman, at 65, was at Oxford UniversityтАЩs mandatory retirement age, but he also knew Chapman did not want to stop working. Wilson flew to a conference he knew Chapman was attending in Pennsylvania in 1950. There, Wilson invited Chapman to Fairbanks to give a few lectures.

Chapman liked the frontier university. After a few of his visits, Wilson named Chapman an honorary fellow of the Geophysical Institute. Chapman agreed to take a position as the instituteтАЩs advisory scientific director.

A reverse-snowbird, Chapman spent only three winter months each year in Fairbanks. His presence sent the trajectory of the institute skyward, both because of his reputation and the fact that he wrote papers with more frequency in his late 60s than he had at Oxford.

Geophysical Institute space physicist Syun-Ichi Akasofu, left, and his mentor Sydney Chapman pause after a walk on the UAF campus in 1962.

While Chapman composed many of those papers in Boulder, Colorado, where he lived and worked at the High-Altitude Observatory for the warmer months of the year, the first affiliation on the papers was тАЬGeophysical Institute, University of Alaska.тАЭ At the many conferences he attended, Chapman wore a name tag with the same label. People noticed.

Years later, after ChapmanтАЩs death in 1970, an obituary writer summed up the manтАЩs influence, describing Chapman as one who possessed тАЬa high talent that draws to itself its own kind тАФ and thereby reincarnates itself and its works.тАЭ

Next week, I will summarize more of the turns of good fortune enjoyed by the Geophysical Institute in its first 75 years.

Since the late 1970s, the ╠└─╖╩╙╞╡' Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. This year is the instituteтАЩs 75th anniversary. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.